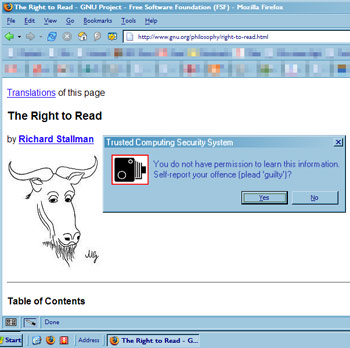

We seem to be accelerating towards the nightmare vision presented by Richard Stallman in his 1997 article, ‘The Right to Read’, ninety years too early, and investigated so thoroughly by Cambridge’s Ross Anderson. (See also here for more discussion of DRM and ‘trusted’ computing).

As reported by InformationWeek:

“Ever since the Trusted Computing Group went public about its plan to put a security chip inside every PC, its members have been denying accusations that the group is really a thinly-disguised conspiracy to embed DRM everywhere. IBM and Microsoft have instead stressed genuinely useful applications, like signing programs to be certain they don’t contain a rootkit. But at this week’s RSA show, Lenovo showed off a system that does use the chips for DRM after all.

[…]

[The] DRM goes beyond encryption. In the system that Lenovo demonstrated, the decision about who can do what with the file is made by whoever generates the PDF, not by the person or organization that owns the laptop. According to Lenovo, the system is also aimed at tracking who reads a document and when, because the chip can report back every access attempt. If you access the file, your fingerprint is recorded.

That might also sound useful, provided of course that you’re the one doing the recording and restricting. (I’d love to be Big Brother! Wouldn’t we all?) The problem is that you won’t be. Even if we forget about media companies for the moment, and assume that DRM is just for businesses that need to protect their sensitive documents from disclosure by employees or outsourcing partners, it’s still a bad tradeoff.”

How different is this really to Stallman’s dystopia?

“In his software class, Dan had learned that each [electronic] book had a copyright monitor that reported when and where it was read, and by whom, to Central Licensing. (They used this information to catch reading pirates, but also to sell personal interest profiles to retailers.) The next time his computer was networked, Central Licensing would find out.”

The comments posted by readers of both the InformationWeek article and the Slashdot post about it explore further some of the implications of this type of technology becoming widespread. I’ll quote a few here making points which particularly struck me:

From Slashdot, by ‘ozmanjusri’:

“The software companies realise they have a product that never gets old, never wears out and will perform the task it was purchased to do until hell freezes over unless they find a way of breaking it. Software companies have been trying to find ways of making software wear out for decades so they can rake a continuous income from their customers the way other manufacturers do. They use product activation to tie the non-wearing software to the fragile hardware for example, but their customers hate them for it.

The customer wants to buy a tool and use it forever, or until they no longer have a use for it, whichever comes first. We know damn well when they’re being scammed, and want nothing to do with this license once and pay forever crap. We’ve tolerated buying the same product over and over again because we accepted we were paying for new features and improvements.

The cost of production of each copy of a program is nil, so the only controllable cost variable for a producer of software is the cost of development, the development of those features and improvements we’ve been paying for. If they can get away with using this DRM garbage to artificially obsolete programs, they won’t need to keep improving the software, they’ll have their continuous income without the cost of development. Say goodbye to software innovation.”

Taking that further is, of course, the point that even when innovative software (and hardware) are developed by smaller companies, there will be no way of using it with the ‘trusted’ hardware that will by that stage be virtually ubiquitous. Architectures of control will retard innovation. As ‘thegrassyknowl’ says, “there are no legitimate uses for this technology that can’t already be accomplished today.”

From Slashdot again, by ‘NemoX’:

[quote from earlier post: “The ***only*** reason consumers aren’t screaming about this yet is because they don’t know it exists, nor how it is incompatable with their expectations about what it means to ‘buy’ something.”]

“By saying “yet”, you imply that you believe people will start screaming about it, at some point. I think you give way too much trust in that the general public is actually educated enough to differentiate between propoganda and the truth. I think they will be fed some load of crap about hackers, and thieves and such. Then the media will help by putting a bunch of it in the news in a timely manner, and all the people will be like “wow there’s a lot of that going on, I understand” then they’ll say my favorite line “…besides, I have nothing to hide, I’m not a thief or a hacker” (which is equivalent to what pastor Martin Niemoller is known for saying). Then they will be forced to pay annual fees and all that nonsense, and continually be told new reasons “why” they have to pay more and more, and the general public will just eat it because, the majority of people are just plain stupid.”

As with so many other issues, the “if you’re not doing anything wrong, you have nothing to fear” argument will, certainly, be brought up every time a proposed architecture of control is criticised. Indeed, I’ve had this levelled at me so often (in the ‘real world’) when I mention what this site’s about, that I intend to respond properly to it with a post in due course. But, going back to the comment, public education is vital. Intrusive DRM needs to be commonly perceived not just as an inconvenience, but as a breach of civil rights.

On the InformationWeek article, ‘Louis’ comments:

“DRM shifts the interpretation of the law from the courthouse into the hardware. You no longer get the reasonable doubt, you no longer get fair use. You get the rights that whoever the writer [is] of that particular DRM gives to you. And since that writer has a vested interest in giving you as little rights as possible, you get just that. Strict minimum, bare essentials (and even then!).

And that’s when the laws are just and equitable from the start. Which they are NOT. In other words, DRM stinks, its application stinks and its power to interpret the law STINKS.”

This is essentially ‘disciplinary architecture‘, or as Andreas Bovens has put it, “every use that is not specifically permitted by the… provider is in fact prohibited.” DRM of this kind is using technology to enforce ‘laws’ (often not actually laws, but just arbitrary sets of conditions) without the benefit of evidence, a jury or due process, and with no way of appealing.

We need a way around all of this. We need TPM-free hardware and enterprise-quality software, whether open source or not, which both ignores and surpasses the DRM’d equivalents. But I’m not optimistic that “the market will provide” when there are artificial constraints put in place (at public expense!) to make the development of such systems illegal (e.g. the DMCA will prevent anyone getting around DRM on documents). I’m worried.

Pingback: Architectures of Control in Design » Philips: You MUST watch these adverts

Pingback: Architectures of Control in Design » Oh yeah, that Windows Kill Switch

Pingback: Architectures of Control in Design » Review: Everyware by Adam Greenfield

Pingback: Some links at fulminate // Architectures of Control