In a world of increasingly complex systems, we could enable social and environmental behaviour change by using IoT-type technologies for practical co-creation and constructionist public engagement.

[This article is cross-posted to Medium, where there are some very useful notes attached by readers]

We’re heading into a world of increasingly complex engineered systems in everyday life, from smart cities, smart electricity grids and networked infrastructure on the one hand, to ourselves, personally, being always connected to each other: it’s not going to be just an Internet of Things, but very much an Internet of Things and People, and Communities, too.

Yet there is a disconnect between the potential quality of life benefits for society, and people’s understanding of these—often invisible—systems around us. How do they work? Who runs them? What can they help me do? How can they help my community?

IoT technology and the ecosystems around it could enable behaviour change for social and environmental sustainability in a wide range of areas, from energy use to civic engagement and empowerment. But the systems need to be intelligible, for people to be engaged and make the most of the opportunities and possibilities for innovation and progress.

They need to be designed with people at the heart of the process, and that means designing with people themselves: practical co-creation, and constructionist public engagement where people can explore these systems and learn how they work in the context of everyday life rather than solely in the abstract visions of city planners and technology companies.

Understanding things

The internet, particularly the world-wide web, has done many things, but something it has done particularly well is to enable us to understand the world around us better. From having the sum of human knowledge in our pockets, to generating conversation and empathy between people who would never otherwise have met, to being able to look up how to fix the washing machine, this connectedness, this interactivity, this understanding, has–quickly–led to changes in everyday life, in social practices, habits, routines, decision processes, behaviour, in huge ways, not always predictably.

It’s surfaced information which existed, but which was difficult to find or see, and–most importantly–links between ideas (as Vannevar Bush, and later Ted Nelson, envisaged), at multiple levels of abstraction, in a way which makes discovery more immediate. And it’s linked people in the process, indeed turned them into creators and curators on a vast scale, of photos, videos, games and writing (short-form and longer). It may not all be hand-coding HTML, but perhaps much of it followed, ultimately, from the ability to ‘View Source’, GeoCities, Xoom, et al, and the inspiration to create, adapt and experiment.

But how do things fit into this? How can the Internet of Things, ambient intelligence and ubiquitous, pervasive computing, help people understand the world better? Could they enable more than just clever home automation-via-apps, more-precisely-targeted behavioural advertising, and remote infrastructure monitoring, and actually help people understand and engage with the complex systems around them—the systems we’re part of, that affect what we do and can do, and are in turn affected by what we do? Even as the networks become ever more complex, can the Internet of Things—together with the wider internet—help people realise what they can do, creating opportunities for new forms of civic engagement and empowerment, of social innovation, of sustainability?

In this article, I’m going to meander a bit back and forth between themes and areas. Please bear with me. And this is very much a draft–a rambling, unfocused draft–on which I really do welcome your comments and suggestions.

Design and behaviour change

For the last few years, I’ve been working in the field of what’s come to be known as design for behaviour change, mostly, more specifically, design for sustainable behaviour. This is all about using the design of systems–interfaces, products, services, environments–to enable, motivate, constrain or otherwise influence people to do things in different ways. The overall intention is social and environmental benefit through ‘behaviour change’, which is, I hope, less baldly top-down and individualist than it may sound. I am much more comfortable at the ‘enable’ end of the spectrum than the ‘constrain’. The more I type the phrase ‘behaviour change’, the less I like it, but it’s politically fashionable and has kept a roof over my head for a few years.

As part of my PhD research, I collected together insights and examples from lots of different disciplines that were relevant, and put them into a ‘design pattern’ form, the Design with Intent toolkit, which lots of people seem to have found useful. All of the patterns exemplify particular models of human behaviour–assumptions about ‘what people are like’, what motivates them, how homogeneous they are in their actions and thoughts, and so on–often conflicting, sometimes optimistic about people, sometimes less so. Each design pattern is essentially an argument about human nature. Some of them are nice, some of them are not.

However, in applying some of the (nicer!) ideas in practice, particularly towards influencing more sustainable behaviour at work and at home, around issues such as office occupancy and food choices, as well as energy use, it became clear that the models of people inherent in many kinds of ‘intervention’ are simply not nuanced enough to address the complexity and diversity of real people, making situated decisions in real-life contexts, embedded in the complex webs of social practices that everyday life entails. (This is, I feel, something also lacking in many current behavioural economics-inspired treatments of complex social issues.)

Many of the issues with the ‘behaviour change’ phenomenon can be characterised as deficiencies in inclusion: the extent to which people who are the ‘targets’ of the behaviour change are included in the design process for those ‘interventions’ (this terminology itself is inappropriate), and the extent to which the diversity and complexity of real people’s lives is reflected and accommodated in the measures proposed and implemented. This suggests that a more participatory process, one in which people co-create whatever it is that is intended to help them change behaviour, is preferable to a top-down approach. Designing with people, rather than for people.

Another issue, noted by Carl DiSalvo, Phoebe Sengers and Hrönn Brynjarsdóttir in 2010, is the distinction between modelling “users as the problem” in the first place, and “solving users’ problems” in approaches to design for behaviour change. The common approach assumes that differences in outcome will result from changes to people–‘if only we can make people more motivated’; ‘if only we can persuade people to do this’; ‘if only people would stop doing that’–overcoming cognitive biases, being more attentive, caring about things, being more thoughtful, and so on.

But considering questions of attitude, beliefs or motivations in isolation rather than in context–the person and the social or environmental situation in which someone acts (following Kurt Lewin and Herbert Simon)–can lead to what is known as the fundamental attribution error. Here, for example, some behaviour exhibited by other people–e.g. driving a short distance from office to library–is attributed to ‘incorrect’ attitudes, laziness, lack of motivation, or ignorance, rather than considering the contextual factors which one might use to explain one’s own behaviour in a similar situation–e.g. needing to carry lots of books (this example courtesy of Deborah Du Nann Winter and Susan M. Koger).

So, framing behaviour change as helping people do things better, rather than trying to ‘overcome irrationality’ as if it were something that exists independently of context, offers a much more positive perspective: solving people’s problems–with them–as a way of enacting behaviour change, from the initial viewpoint of trying to understand, in context, the problems that people are trying to solve or overcome in everyday life, rather than adopting a model of defects in people’s attitudes or motivation which need to be ‘fixed’.

Something that has arisen, for me, during ethnographic research and other contextual enquiry around things like interaction with heating systems, energy (electricity and gas) use more widely—and even seemingly unrelated issues such as neighbourhood planning, or a community group’s use of DropBox—is the importance of people’s understanding and perceptions of the systems around them. Questions about perceived agency, mental models of how things work, assumptions about what affects what, conflating one concept or entity with another, and so on, feed into our decision processes, and the differences in understanding can cause conflict or undesired outcomes for different actors within the system.

As Dan Hill puts it, if we can “connect [people’s] behaviour to the performance of the wider systems they exist within” we can help them “begin to understand the relationships between individuals, communities, environments and systems in more detail”.

But it seems as though most approaches to design for behaviour change–and it’s a rapidly growing field under different labels–either ignore questions around understanding entirely, or try to find out about how users (mis)understand things, and then attempt to change users’ understanding to make it ‘correct’. Many, in fact, start straight out to try to change understanding without trying to find anything out about users’ current understanding. A few (but not enough, perhaps) try to adjust the way a system works so that it matches users’ understanding. (This is a development of something I explored in a London IA talk a few years ago.)

Also, I must emphasise at this point that ‘behaviour change’ is not really a thing at all. ‘People doing something differently’ covers so much, across so many fields and contexts, that it’s silly to think it can be assessed properly in a simple way.

If anyone is really an ‘expert’ in ‘behaviour change’, it is parents and teachers and wise elderly raconteurs of lives well lived, children with youthful clarity of insight, people who strike up conversations with strangers on the bus, or talk down people about to jump off bridges: optimistic, experienced (or not) human students of human nature, not someone who sees ‘the public’ as a separate category to him- or herself, ripe for ‘intervention’.

The Internet of Things as an innovation space

One of the nicest things about the Internet of Things phenomenon–and indeed the Quantified Self movement–as opposed to that other, related, topic of our time, the top-down ‘Smart City’, is the extent to which it crosses over with the bottom-up, almost democratic, Maker movement mentality. I’m using ‘the IoT’ here as a broad category for the potential to involve objects and sensors and networks in areas or situations that previously didn’t have them.

The Internet of Things, through initiatives such as Alexandra Deschamps-Sonsino’s IoT meetups and others–while undoubtedly boosted commercially by Gartner Hype Cycle-baiting corporate buzzword PowerPoints–has been to no small extent driven by people doing this stuff for themselves. And helping each other to do it better. The peer support for anyone interested in getting into this area is immense and impressive: you can bet that someone out there will offer assistance, suggest ways round a problem, and share their experience. The barriers to entry are relatively low, and there are organisations and projects springing up whose rationale is based around lowering those barriers further.

The IoT is a huge von Hippel user innovation space, and it involves not just innovation by users, but innovation that is about building things. Its very sustenance is people building things to try out hypotheses, addressing and reframing their own problems responding to their own everyday contexts, modifying and iterating and joining and forking and evolving what they’re doing, putting the output from one project into the input of another, often someone else’s. And yet it is still quite a small community in a global sense, overrepresented in the echo-chamber of the sorts of people likely to be reading this article.

Constructionism and co-creation

I suspect there is something about the open structure of many IoT technologies (and those which have enabled it) which has made this kind of distributed, collaborative community of builders and testers and people with ideas more likely to happen. It may just be the openness, but I think it’s more than that. There are three other elements which might be important:

- Linking the real world to a virtual, abstract, invisible one. Even if an IoT project is about translating one physical phenomenon into another, this action comes about through links to an invisible world. I don’t know for certain why that might be important, but I think it may be that it triggers thinking about how the system works, in a way that is still somewhat outside our everyday experience. This kind of action-at-a-distance retains some magic, in the process calling new mental models or simulations into existence…

- …which are then tested and iterated, because nothing ever works first time. This means people learn through doing things, through coming up with ideas about how things work, and testing those hypotheses by their own hand, often understanding things at quite different levels of abstraction (but that still being just fine). It’s not a field that’s particularly suited to learning from a book (despite some excellent contributions)…

- …and indeed the boundaries of what the IoT is for are so fluid and expansive in a ‘What use is a baby?’ sense that the goal is one of exploration rather than ‘mastery’ of the subject. There is no right or wrong way to do a lot of this stuff, nor limits imposed by any kind of central authority.

I’m no scholar of educational theory, but it seems that these kinds of characteristics are similar to what Seymour Papert, father of LOGO and student of Jean Piaget, termed constructionism–in the words of the One Laptop Per Child project,

“a philosophy of education in which children learn by doing and making in a public, guided, collaborative process including feedback from peers, not just from teachers. They explore and discover instead of being force fed information”.

Constructionist learning (whether with children or adults) is not a ‘leave them to it’ approach: it involves a significant degree of facilitation, including designing the tools (like LOGO, or Scratch) that enable people to create tools for themselves. Returning to the design context, this is a central issue in discussions of participatory design, co-design and co-creation–to what extent, and how, designers are most usefully involved in the process. What are the boundaries of co-creation? How do they differ in different contexts? Is the progression from design for people to design with people to design by people an inevitability? Whither the designer in the end case?

Setting aside this kind of debate for the moment, I am going to say that for the purposes of this article:

- involving people (‘users’, though they are more than that) in a design process…

- to address problems which are meaningful for them, in their life contexts…

- in which they participate through making, testing and modifying systems or parts of systems…

- partly facilitated or supported by designers or ‘experts’…

- in a way which improves people’s understanding of the systems they’re engaging with, and issues surrounding them…

meets a definition of ‘constructionist co-creation’.

Behaviour change through constructionist co-creation

Now, let’s go back to behaviour change. I mentioned earlier my contention that much of what’s wrong with the ‘behaviour change’ phenomenon is about deficiencies in inclusion. People (‘the public’) are so often seen as targets to have behaviour change ‘done to them’, rather than being included in the design process. This means that the design ‘interventions’ developed end up being designed for a stereotyped, fictional model of the public rather than the nuanced reality.

Every discipline which deals with people, however tangentially, has its own models of human behaviour–assumptions about how people will act, what people are ‘like’, and how to get them to do something different (as Susan Weinschenk notes). As Adam Greenfield puts it:

“Every technology and every ensemble of technologies encodes a hypothesis about human behaviour”.

All design is about modelling situations, as Hugh Dubberly and Paul Pangaro and before them, Christopher Alexander remind us. Even design which does not explicitly consider a ‘user’ inevitably models human behaviour in some way, even if by omitting to consider people. Modelling inescapably has limitations–Chris Argyris and Donald Schön suggested that “an interventionist is a man struggling to make his model of man come true”–but of course, although “all models are wrong…, some are useful.”

In design for behaviour change, we need to recognise the limitations of our models, and be much clearer about the assumptions we are making about behaviour. We also need to recognise the diversity and heterogeneity of people, across cultures, across different levels of need and ability, but also across situations. This approach is something like attempting to engage with the complexity of real life rather than simplifying it away–in Steve Portigal’s words:

“rather than create distancing caricatures, tell stories… Look for ways to represent what you’ve learned in a way that maintains the messiness of actual human beings.”

What’s a way to do this? Co-creation, co-production–in a behaviour change context–enables us to include a more diverse set of people, leading to a more nuanced treatment of everyday life. This, in itself, represents an advance in inclusion terms over much work in this field. Flora Bowden and I have tried to take this approach as part of our work on the European SusLab energy project.

But going further, constructionist co-creation for behaviour change would enable people actually to create, test, iterate and refine tools for understanding, and influencing, their own behaviour. Just look at Lifehacker or LifeProTips, GetMotivated or even the venerable 43 Folders. People enjoy exploring ways to change their own behaviour, through experimenting, through discussion with others, and through developing their own tools and adapting others’, to help understand themselves and other people, and the systems of everyday life which affect what we do. Behaviour change could be direct–or it could be, perhaps more interestingly, directed towards exploring and improving our understanding of the systems around us.

Invisible infrastructures and the Internet of Things: avoiding the demon-haunted smart fridge

The thing is, the systems around us are complex and becoming more so, and often invisible–or “distressingly opaque”–in the process, which makes them more difficult to understand and engage with. This includes everything from ‘the Cloud’ (which, as Dan Hon notes, is coming to the fore with news stories such as celebrity photo hacking) to Facebook (as danah boyd puts it, “as the public, we can only guess what the black box is doing”) to CCTV and other urban sensor networks.

(Right: An interesting infrastructure ‘business model’ from the Public Safety Charitable Trust–see http://www.elyplace.com/bluetooth-rates-avoidance-scheme-fails/)

(Right: An interesting infrastructure ‘business model’ from the Public Safety Charitable Trust–see http://www.elyplace.com/bluetooth-rates-avoidance-scheme-fails/)

Timo Arnall, in his PhD thesis, introduces this issue using the example of smartphones, “perhaps the most visible aspect of contemporary, digitally-mediated, everyday-life. Yet the complex networks of systems and infrastructures that allow a smartphone to operate remain largely invisible and unknown.”

He goes on to explore, via some beautiful projects, another invisible infrastructure–RFID and near-field communication– and the possibilities of making this visible, tangible and legible.

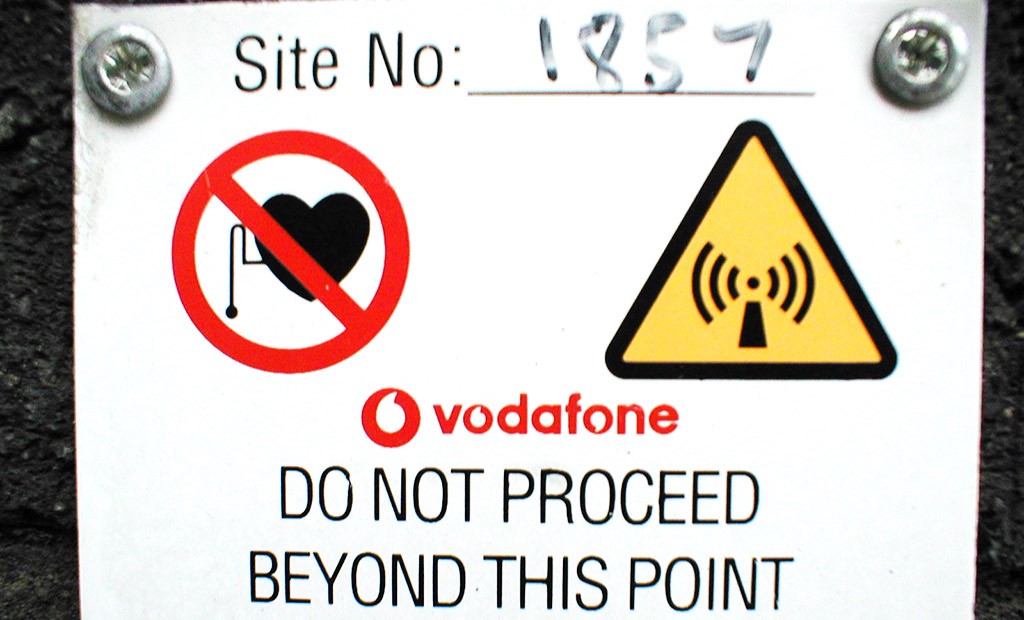

Most diagrams or infographics aiming to illustrate the Internet of Things show visible lines connecting objects to each other, or to central hubs of some kind. But whatever forms the IoT takes, most of these are going to be ‘invisible by default’, in Mayo Nissen’s words (specifically referring to urban sensors). Invisibility might seem attractive, and magic (and we’ll get onto seamlessness in a bit) but by its very nature it conceals the links between things, between organisations, between people and purpose:

“Some sensing technologies capture our imagination and attract our constant attention. Yet many go unnoticed, their insides packed with unknowable electronic components, ceaselessly counting, measuring, and transmitting. For what purpose, or to whose gain, is often unclear… there is seldom any information to explain what these barnacles of our urban landscape are or what they are doing.”

(Above and below: Black boxes and mental models: an exercise at dConstruct 2011. Some photos by Sadhna Jain.)

Back in 2011 I ran a workshop at dConstruct including an exercise where groups each received a ‘black box’, an unknown electronic device with an unlabelled interface of buttons, ‘volume’ controls and LEDs, housed in a Poundland lunchbox and badly assembled one evening while watching a Bill Hicks documentary and drinking whisky.

Internally —and so secretly—each box also contained a wireless transmitter, receiver, sound chip and speaker (basically, a wireless doorbell), and in one box, an extra klaxon. The aim was to work out what was going on—what did the controls do?—and record your group’s understanding, or mental model, or even an algorithm of how the system worked in some form that could explain it to a new user who hadn’t been able to experiment with the device.

Internally —and so secretly—each box also contained a wireless transmitter, receiver, sound chip and speaker (basically, a wireless doorbell), and in one box, an extra klaxon. The aim was to work out what was going on—what did the controls do?—and record your group’s understanding, or mental model, or even an algorithm of how the system worked in some form that could explain it to a new user who hadn’t been able to experiment with the device.

As people realised that the boxes ‘interacted’ with each other, by setting off sounds in response to particular button-presses, the groups’ explanations became more complex.

Each group used slightly different methods to investigate and illustrate the model, with unexpected behaviour or coincidences (one group’s box setting off the doorbell in another, but coinciding with a button being pressed or a volume control being turned) leading to some rapidly escalating complex algorithms.

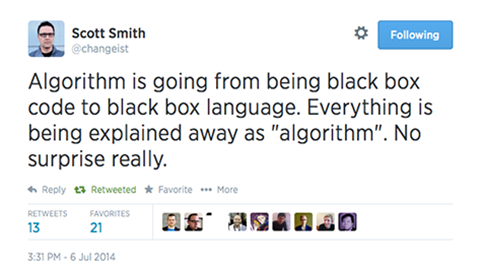

We are now creating an even more complex world of black boxes, networked black boxes with their own algorithms, real and assumed, and those that depend on algorithms out of our hands, remote, changeable, strategic, life-changing which we may not have any easy way of investigating. And which model us, the public, in particular ways.

(“Algorithm is going from black box code to black box language. Everything is being explained away as “algorithm”. No surprise really.” Scott Smith, 6 July 2014—https://twitter.com/changeist/status/48579323239650918)

As James Bridle puts it, “comprehension is impossible without visibility”:

“the intangibility of contemporary networks conceals the true extent of their operation… This invisibility extends through physical, virtual, and legal spaces.”

Bridle is talking about a policing context, but invisibility, or rather lack of transparency, is of course also a hallmark of crime and corruption, often intentionally complex systems. Dieter Zinnbauer’s concept of ambient accountability is very relevant here: systems can only be accountable if people can understand them, whether that’s windows in building-site hoardings or politicians’ expenses.

Or as Louise Downe has said:

“We can only trust something if we think we know how it works… When we don’t know how a thing works we make it up.”

What new superstitions are going to arise from smart homes, smart meters, smart cities? What will people make up? Are my fridge and Fitbit collaborating with Tesco and BUPA to increase my health insurance premiums? What assumptions are the systems in my daily life going to be making about me? How will I know? What are the urban legends going to be? How will this understanding affect people’s lives? How can we make use of what the IoT enables to help us understand things, rather than making things less understandable?

An opportunity

The opportunity exists, then, for more work which uses a constructionist approach to enable us–the public–to investigate and understand the complex hidden systems in the world around us, in the process potentially changing our mental models, behaviour and practice. Tools based around IoT technology, developed and applied practically through a process of co-creation with the public, could enable this particularly well. In general, co-creation offers lots of opportunities for designing behaviour change support systems that actually respond to the real contexts of everyday life. But the IoT, in particular, can enable technological participation in this.

We would have to start with particular domains where public understanding of a complex, invisible system in everyday life potentially has effects on behaviour or social practices, and where changing that understanding would improve quality of life and/or provide social or environmental benefit.

Introducing ‘knopen’

I want to propose some examples of projects (or rather areas of practical research) that could be done in this vein, but before that–because I can–I am going to coin a new word for this. Knopen, a fairly obvious portmanteau of know and open, can be a verb (to knopen something) or an adjective (e.g. a knopen tool). Let’s say ‘to knopen’ conjugates like ‘to open’. We knopen, we knopened, we are knopening. Maybe it will usually be more useful as a transitive verb: We knopened the office heating system. The app helped us knopen the local council’s consultation process. Help me knopen the sewage system. Maybe it’s useful as a gerund: knopening as a concept in itself. Knopening the intricacies of the railway ticketing system has saved our family lots of money.

Tools for understanding

What does knopen mean, though? I’m envisaging it being the kind of word that’s used as description of what a tool does. We have tools for opening things–prying, prising, unscrewing, jimmying, breaking, and so on. We also have tools that help us know more about things, and potentially understand them–a magnifying glass, a compass, Wikipedia–but just as with any tool, they are better matched to some jobs than to others.

If I just use a screwdriver to unscrew or pry open the casing on my smart energy meter, and look at the circuitboard with a magnifying glass, unless I already have lots of experience, I don’t know much more about how it works, or what data it sends (and receives), and why, or what the consequences are of that. I don’t necessarily have a better understanding of the system, or the assumptions and models inscribed in it. I have opened the smart meter, but I haven’t knopened it. To knopen it would need a different kind of tool. In this case, it might be a tool that interrogates the meter, and translates the data, and the contexts of how it’s used and why, into a form I understand. That doesn’t necessarily just mean a visual display.

This, then, would be knopening: opening a system or part of a system (metaphorically or physically) with tools which enable you to know and understand more about how it works, what it does, or the wider context of its use and existence: why things are as they are. Knopening could include ‘knopening thyself’–understanding and reflecting on why and how you make decisions.

Knopening isn’t as involved as grokking. To grok something is at a much deeper level. Nevertheless, knopening could be transformative. Going back to the earlier discussion, knopening is basically a label for a process by which we can investigate and understand the complex hidden systems in the world around us, which could certainly change our mental models, behaviour and practice. Knopening is about understanding why.

Maybe knopen is a daft conceit, a ‘fetch’ that isn’t going to happen. But it’s worth a try. And I see that it also means ‘to button’ or ‘to knot’ in Dutch, but that’s not too awful. As my wife put it, “that’s quite sweet.” Probably ontknopen, unbuttoning or untying, would be closer in meaning to what I mean. Urban Dictionary tells us that knopen can also mean “the act of knocking on and opening a closed door simultaneously”, which is not inappropriate, I think.

Some areas of research for knopen

These are all about people making and using tools to understand–to knopen–the systems around them, in particular the whys behind how things work. They all have the potential to integrate the quantitative data from networked objects and sensors with qualitative insights from people themselves, in co-created useful and meaningful ways.

DIY for the home of the future

In the UK, “at least 60% of the houses we’ll be living in by 2050 have already been built” (and that quote’s from 2010). That means that whatever IoT technologies come to our homes, they will largely be retrofitted. The ‘smart home’ in practice is going to be piecemeal for most people, the Discman-to-cassette-adaptor-to-car-radio rather than a glossy integrated vision.

(Photo by Toyohara, used under a Creative Commons licence)

That’s something to bear in mind in itself, but even with this piecemeal nature, there’s still going to be plenty of invisibility–quite apart from whatever it is our fridges are going to be making decisions about, what will DIY look like?

What are people going to be able to choose to fit themselves? What systems will people be able to connect together? What’s the equivalent of a buried cable detector for data flows? What will Saturday afternoons be like with the IoT? Is it an electrician we need or a ‘data plumber’? What will happen when parts need to be replaced? When smart grids come along, for example, what is interaction with them going to look like? Can DIY work in that context? What happens if microgeneration becomes popular?

Could we use this DIY context strategically—as a way of engaging people in behaviour change, through active participation in experimenting and changing their own homes and everyday practices, using IoT technologies? How do we domesticate the IoT?

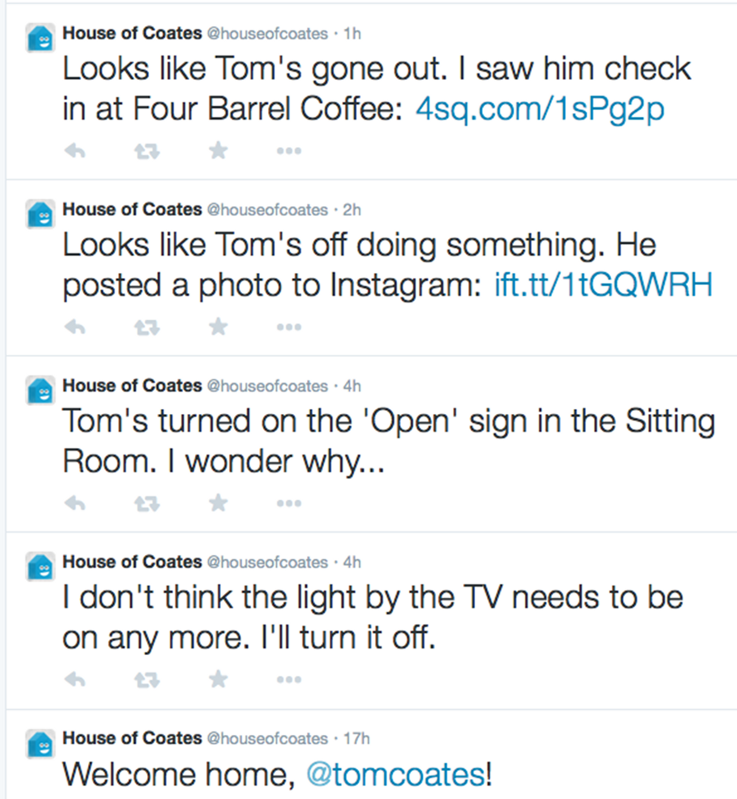

(Tom Coates’ House of Coates, and the Haunted Coates House)

Something in this space could be the core of the knopen concept: tools that enable us to understand and investigate the invisible systems around us, and the links between them, at home (or at work). Really basically, we could think of it as in-context system diagrams on everything – not just static, but explorable explanations in Bret Victor’s terminology, maybe even some kind of data traces. And those explanations don’t have to be physical diagrams—they can be ambient, responsive, exploring both the backstories and possible future states of systems.

Networked devices and sensors, inputs and outputs, everything the IoT provides, could show us explicitly how systems work both in and beyond our immediate home context—including our own actions, past, present and future (hence enabling us to change our behaviour), and those of other people. We would learn what a system assumes/knows about us, and how it makes decisions that affect us and others; how do we fit into these systems that pervade our homes?

Seams, streams and new metaphors

The idea of seamful design  – in contrast to the seamlessness which so often seems to be goal of advances in human-computer interaction–is useful here. We are used to systems being promoted as invisible, seamless, frictionless as if this is necessarily always a good thing, from contactless payment to Facebook Connect. There’s no doubt that seamlessness can be convenient, but there’s a cost.

Matthew Chalmers, who has developed the ideas that Mark Weiser (father of calm technology, ubiquitous computing, etc) had around seamlessness and seamfulness, suggests that: “Seamfully integrated tools would maintain the unique characteristics of each tool, through transformations that retained their individual characteristics.”

Going slightly further than that, perhaps, by enabling people to experience the joins between systems, and the discontinuities, the texture of technologies—even making the seams not just ‘beautiful’ but tangible– we could help them understand better what’s going on, and interact with systems in a different way. As Karin Andersson says:

“The seams that are the most important are the ones that can improve a system’s functionality and when they are understood and figured out how they can become a resource for interaction by the user. If designers know how certain seams affect interactions, they can then incorporate them into an application and direct their effects into useful features of the system. This way, seamful design allows users to use seams, accommodate them and even exploit them to their own advantage”

Knopen is perhaps an attempt to enable people to make tools to make seams visible, or tangible, for themselves, where currently they are not. It is trying to turn seamlessness into seamfulness, then into understanding and empowerment, through enabling, facilitating, investigation of those systems: brass rubbing for the systems of the home, perhaps.

(Detail of Juliana, wife of Thomas de Cruwe, 1411. CC licensed by Amanda Slater)

Seams are important to mental models. In the 1990s, Neville Moray—drawing on a approach taken by cybernetician (and ‘requisite variety’ originator) Ross Ashby—explored how one way of modelling what a mental model really is, is a lattice-like network of nodes that are super- or subordinate to other nodes (not necessarily in the sense of power relations, but rather in terms of parts or categories). By this interpretation, different mental models of the same situation or system come down to things like:

- two people’s models containing different sets of nodes

- or, more specifically, conflating particular nodes or introducing distinctions between nodes where others treat them as the same thing

- two people’s models connecting the same nodes in different ways

Seams are, perhaps, the links or gaps between nodes or groups of nodes. Intentional seamlessness is an attempt to hide these links or gaps by actually conflating particular nodes or groups of nodes from the user’s perspective. Seamlessness is saying, “This is one system, and these nodes are the same”. In doing this, it inherently removes the ability to see or inspect or question or understand these relations.

We are—and will shortly be even more so—surrounded by systems, in our homes and elsewhere, that are collecting, sending, receiving and storing data all the time, about us, our actions and our environments. And yet we are generally not privy to what’s going on, what decisions are being made, where the data come from and where they go.

It might not seem a major issue at present to most people—even in the light of Snowden’s revelations and all that’s come since  – but once, for example, smart meters are dynamically adjusting pricing for electricity and gas on a large scale, a greater number of people are going to want to understand where those prices are coming from, and how these systems work. Compare the—often amusing—reactions when people explore what Google Ads or Facebook thinks it knows about them. Many people seem to enjoy this kind of exploration—all the more reason for a constructionist approach.

We need a narrative context for the streams in our daily lives: what is the story of the sensors? What is the meaning of what’s going on? Even a Dyson-style ‘transparent container’ metaphor for data, showing us what’s being collected, or colour-coded statuses on devices, would give us some more understanding. This is something like ambient accountability in Dieter Zinnbauer’s terminology, but involving us, the public, the ‘end user’, much more explicitly.

Metaphors could play an important role here, or perhaps new metaphors. Representing a new, unfamiliar system in terms of more familiar ones is maybe obvious, and has its limitations (except in Borges, the map is never the territory), but as with our discussion of new superstitions earlier, it’s almost inevitable that new metaphors will arise for parts of these invisible systems in the home and elsewhere, as part of mental models and in people’s explanations to others of how they work. Metaphors are very commonly used in design for behaviour change, from gardens to sarcastic overlords.

(What does energy look like? From the V&A Digital Design Weekend 2014. Photo by V&A Digital.)

We can learn quite a lot from exploring people’s understanding and mental imagery around invisible systems. A project Flora Bowden and I have been doing over the last couple of years involves asking people to draw ‘what energy looks like’; we’ve also tried it with concepts such as ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’, and there are large scale projects such as Can You Draw the Internet? There are insights for the design of new kinds of interfaces, of course, but also something more fundamental about how people perceive and relate to intangible things. Almost by definition, people use metaphors (or metonyms) of one kind or another to visualise abstract or unseen concepts—what would they look like for invisible systems in our homes?

Could we use new metaphors strategically, to help people understand new systems? What should they be? How do they link to behaviour change in this context? Bringing it back to DIY, what metaphors are going to be used to get people interested in fitting these systems to their homes in the first place?

You’re not alone

Moving away from the home, this next group of ideas would use IoT technologies to enable ‘peer support’ for decision making: connecting people to others facing similar situations, and enabling people to understand each other’s thinking and what worked for them (or not). The aim of this knopening of situations would be empathy, but also practical advice and support.

Understanding–and reflecting on–how you think, and how other people approach the same kinds of situation, can help change mental models, support behaviour change in the context of everyday practices (learning from others what worked for them, and why), and tackle attribution errors, as mentioned earlier, by bridging the gaps between our own thinking and our assumptions about others’ behaviour.

The contexts and domains where this could be useful range from physical and mental health, to route planning, to home improvement, to financial decisions, to any situation where a combination of networked objects and/or sensors, combined with qualitative insights from people who are part of the system, could help.

Some specific ways of implementing You’re not alone might include:

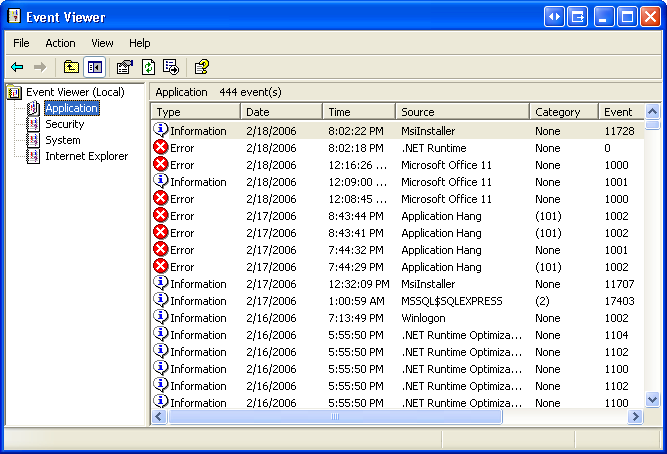

(Windows XP Event Viewer—image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Event_Viewer)

The Shared ‘Why?’

- This would be a tool for annotating situations with ‘what your thinking is’ as you do things (that may be logged automatically anyway)—a kind of ‘Why?’ column in the event logs of everyday life.

- The question might be prompted automatically by certain situations being recognised (through sensor data) or could also be something you choose to record. These ‘Whys’ would then be available to your future self, and others (as you choose) when similar situations arise.

- My thinking here is that (as Tricia Wang points out), the vast quantities of Big Data generated and logged by devices, sensors and homes and infrastructure, are largely devoid of human contexts–the ‘Why?’, the ‘thick’ data–that would give them meaning. There’s a great opportunity for introducing a system which makes this easier to capture. It could be an academic or design practitioner research tool, but my main priority is that it be actually useful to the people using it.

(Annotating household objects to understand thermal comfort. From a study by Sara Renström and Ulrike Rahe at Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg.)

- Asking people to annotate real-life situations with simple paper labels or arrows has worked well as a research method for eliciting people’s stories, meanings and thought processes around interaction with particular devices, and the sequences they go through. Similarly, even simple laddering or 5 Whys-type methods can be used to uncover people’s heuristics around everyday activities. But how could these kinds of methods be made more useful for those doing the annotation or answering the questions–and for others too?

- While there exist research methods such as experience sampling and sentiment mapping, with plenty of location- or other trigger-based mobile apps, these largely focus on mood and feelings, rather than the potentially richer question of ‘Why?’. Yet Facebook and Twitter have shown us that short-form status updates, with actual content (mostly!), are something people enjoy producing and sharing with others. When I worked on the CarbonCulture at DECC project, one of the most successful features (in terms of engagement) of the OK Commuter travel logging app was a question prompting users to describe that morning’s commute with a single word, which often turned out to be witty, insightful and revealing of intra-office dynamics around topics such as provision of facilities for cyclists.

- Clearly there are lots of questions here about validity and privacy. Would people only log ‘Whys’ that they wanted others to know? Who would have access to my ‘Whys’? Would they ‘work’ better in terms of empathy or behaviour change if linked to real names or avatars than anonymously? We would have to find ways of addressing and accommodating these issues.

There are some parallels with explicitly social projects such as the RSA’s Social Mirror Community Prescriptions, but also with work in naturalistic decision making. For example, there are projects exploring how Gary Klein’s recognition-primed decision model of how experts make decisions (based on a mixture of situational pattern recognition and rapid mental simulation) can be ‘taught’ to non-experts. A constructionist approach seems very appropriate here.

Helpful ghosts: ambient peer support

- What this would involve is essentially being able to create helpful ‘ghosts’ for other people, which would appear when certain situations or circumstances, or conjunctions of conditions, were detected, through IoT capabilities. You could record advice, explanations, warnings, suggestions, motivational messages, how-to guides, photos, videos, audio, text, sets of rules, anything you like, which would be triggered by the system detecting someone encountering the particular conditions you specified. That could be location-based, but it could also be any other condition. It’s almost like a nice version of leaving a note for your successor, or anyone who faces a similar situation.

(The Stone Tape (BBC, 1972). Image from http://anamericanviewofbritishsciencefiction.com/2013/12/16/the-stone-tape-1972/)

- The ghosts wouldn’t be scary, or at least I hope not. Maybe ghost is the wrong word. The idea obviously has parallels with Marley’s Ghost in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol–and the feedforward / scenario planning / design futures of the Ghost of Christmas Yet-To-Come–but what directly inspired me was Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape (probably in turn inspired by archaeologist and parapsychologist Tom Lethbridge’s work), in which ghosts are explained as a form of recording somehow left behind in the fabric of buildings or locations where strong emotions have been felt. Kevin Slavin’s talk at dConstruct 2011, and Tom Armitage’s ghostcar, are also inspirations here. And I have recently also come across Joe Reinsel’s work on Sound Cairns, which has some very clever elements to it.

- Maybe it’s better to think of this like If This Then That (see below), but allowing you to create rules that trigger events for other people instead of just for you.

- How would it be different to Clippy? (thanks to Justin Pickard for making this connection). We should aim to learn from the late Clifford Nass’s work at Stanford on why Clippy was so disliked, and how to make him more loveable. It would also be important that the helpful ghosts did not just become a form of ‘pop-up window for real life’. Advertisers should not be able to get hold of it. It should always be opt-in, and the emphasis should be on participation (creating your own ghosts in response) and understanding. It is meant to be at least a dialogue, a collaborative approach to learning more about, and understanding–knopening–a situation, and then passing on that understanding to others.

A Collective If This Then That

- This is probably already possible to achieve with clever use of If This Then That together with some other linked services, but the basic idea would be a system where multiple people’s inputs–which could be a combination of quantitative sensor data and qualitative comments or expressions of sentiment or opinion–together can trigger particular outputs. These might also be collective, or might apply only in a single location or context.

- There are obvious top-down examples around things like adaptive traffic management, but it would more interesting to see what ‘recipes’ emerge from people’s–and communities’–own needs. There could also be multiple outputs to different systems. They could work within a family or household or on a much bigger scale–connecting families who are often apart, for example.

- The knopen element comes with being able to understand–right from the start–how to make action happen, and collaboratively create recipes which address a community’s needs, for example. The system might be complex but would be not only visible, but fully accessible since the participants would be involved in creating and iterating it.

- It could involve ‘voting’ somehow, but it would also be interesting to see effects emerge from unconscious action or a combination of physical effects read by sensors and social or psychological effects from people themselves.

- I’m inspired here particularly by Brian Boyer and Dan Hill’s Brickstarter–in which the collective desire/need/interest of the crowdfunding model is applied to urban infrastructure–but also by the academic research (and workshop at Interaction 12) I did exploring ‘if…then’-type rules of thumb and heuristics that people use for themselves, often implicitly, around things like heating systems, and how different people’s heuristics differ.

- There’s some really interesting academic research going on at the moment by teams at Brown and Carnegie Mellon–e.g. see this paper by Blase Ur et al from CHI 2014–on using IFTTT-like ‘practical action-trigger programming’ in smart homes as a way to enable a more easily programmable world, and it would be great to explore the potential of this approach for improving understanding and engagement with the systems around us. As Michael Littman puts it:

“We live in a world now that’s populated by machines that are supposed to make our lives easier, but we can’t talk to them. Everybody out there should be able to tell their machines what to do.” (Professor Michael Littman, Brown University)

Storytelling for systems: Five whys for public life

‘Five whys’ is a method for what’s called root cause analysis, used in fields as diverse as quality management and healthcare process reform. It’s similar to the interview technique of laddering, which has seen some application in user experience design. The basic principle is that there is never only one ‘correct’ reason ‘Why?’ something happens: there are always multiple levels of abstraction, multiple levels of explanation, multiple contexts–and each explanation may be completely valid within the particular context of analysis. In ‘solving’ the problem, the repeated asking ‘Why?’ enables reframing the problem at further levels up (or down) this abstraction hierarchy, as well as giving us the ‘backstory’ of the current state (which is often considered to be a problem, hence the analysis).

It’s a practical instantiation, in a way, of Eliel and Eero Saarinen’s tenet of trying to design for the “next largest context–a chair in a room, a room in a house, a house in an environment, environment in a city plan”. In some previous work, I tried exploring (not particularly clearly), the notion that this kind of approach, in reframing the problem at multiple levels, could essentially provide us with multiple suggested ‘solutions’ by inverting problem statements at each level of abstraction.

So what do we do with this? How can IoT technology be useful? Imagine being able to ‘ask’ the physical and societal infrastructure around you–the street lamps, the building site, the park fountain, but also the local council, the voting booth, the tax office, your children’s primary school’s board of governors, the bus timetable, Starbucks, the numberplate recognition camera, the drain cover, the air quality sensors in the park, the National Rail Conditions of Carriage–Why?

So what do we do with this? How can IoT technology be useful? Imagine being able to ‘ask’ the physical and societal infrastructure around you–the street lamps, the building site, the park fountain, but also the local council, the voting booth, the tax office, your children’s primary school’s board of governors, the bus timetable, Starbucks, the numberplate recognition camera, the drain cover, the air quality sensors in the park, the National Rail Conditions of Carriage–Why?

Why are they set up the way they are? Who came up with the idea? (not for blame, but for empathy). What’s the story behind the systems? What influenced how they’re operating, how the decisions were made, how they came to be?

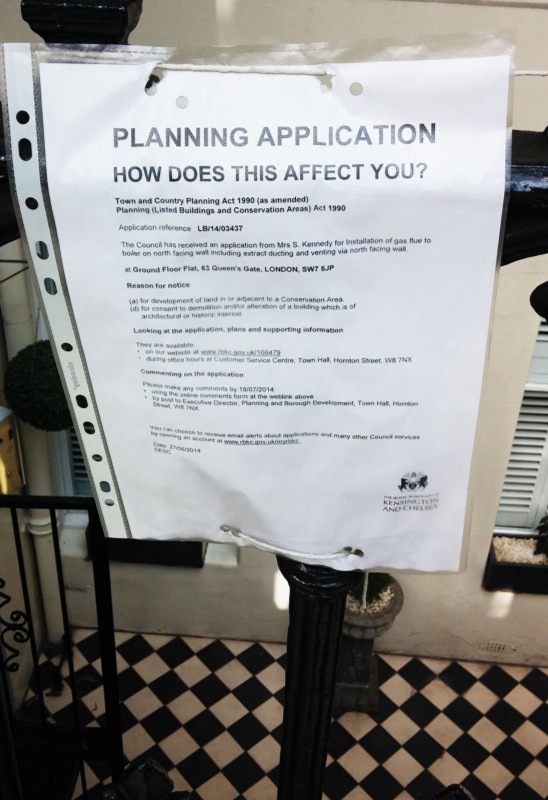

What data do they collect, and what do they do with the data? What’s the revision history for this government policy? What were the reasons given for that cycle path being routed that way? What’s the history of planning applications for buildings on this site? What were the debates that led to the current situation?

And for each of those, the answers would be explained at multiple levels–maybe not exactly five ‘whys’, but more than one simplistic reason, devoid of context.

This isn’t just Freedom of Information–although it intersects with that. It’s more about understanding the decision process, the constraints and priorities others have had to contend with along the way. Kind of autobiographies for systems (including public objects, perhaps, but also institutions–maybe even Dan Hill’s ‘Dark Matter’). Or a cross between blue plaques (or rather, Open Plaques), ‘For the want of a nail’, WhatDoTheyKnow, City-Insights, FixMyStreet, Dieter Zinnbauer’s Ambient Accountability, TheyWorkForYou, Historypin, Wikipedia’s revision history, Mayo Nissen’s ‘Unseen Sensors’ and a sort of transparent reverse IFTTT where you can see what led to what.

From a technology point of view, you could do it very simply with smartphones and QR codes or NFC tags stuck on bits of street furniture (for example), but it would be possible to do much more when systems have a networked capability and presence–when data are being collected or received, or transmitted, or when one piece of infrastructure is informing another.

Of course, it could be seen as quite antagonistic to authority: this kind of transparent storytelling could reveal how inept some institutions–and potentially some individuals–are at making decisions, although it could also help generate empathy for people facing tough decisions, in the sense of revealing the trade-offs they have to make, and so increase public engagement with these systems by showing both their complexity (potentially) and their human side. Peerveillance, sousveillance, equiveillance, yes–but preferably framed as storytelling.

The challenge would be finding positive stories to lead with (thanks to Duncan Wilson for this point). Suggestions are very welcome.

Conclusion: what next?

This has been a long, rambling and poorly focused article. It tangles together a lot of ideas that have been on my mind, and others’ minds, for a while, and I’m not sure the tangle itself is very legible. But I welcome your comments.

My basic thesis is that IoT technology can be a tool for behaviour change for social and environmental benefit, through involving people in making systems which address problems that are meaningful for them, and which improve understanding of the wider systems they’re engaging with.

I think we can do this, but, as always, doing something is worth more than talking about it. As an academic, I ought to be in a position to find funding and partners to do something interesting here. So I am going to try: if you’re interested, please do get in touch.