Back in September we looked at Mentor Teaching Machines, a clever type of non-linear textbook from the early 1970s which guides/constrains the user’s progression, in the process diagnosing some common types of misunderstanding and ‘remedying’ them. The comments were enlightening, too: there’s a lot more history to programmed teaching texts and programmed instruction than I realised, and I will certainly be covering some of this, and what useful design principles and inspiration can be drawn from it, at some point.

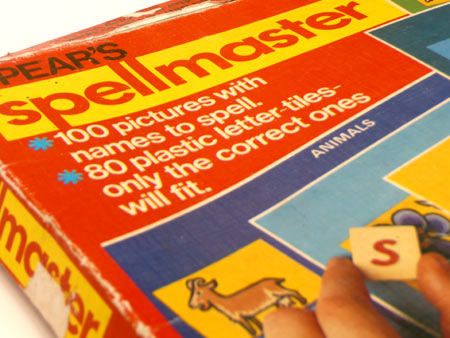

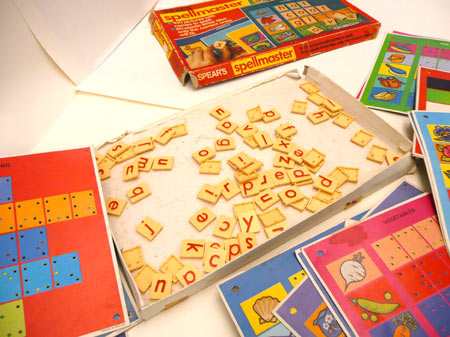

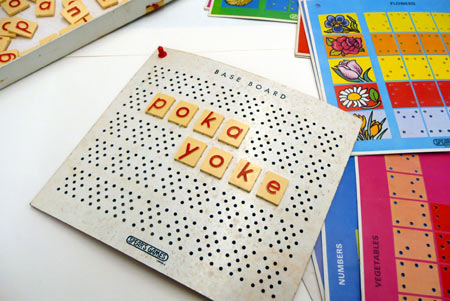

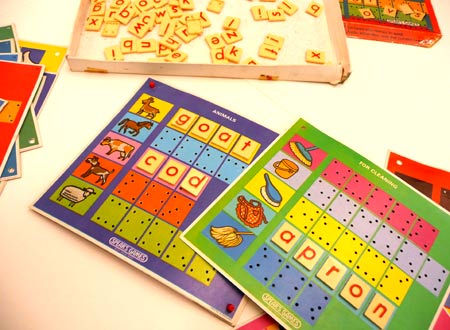

Now, this is not in the same league, but interesting nonetheless: a ‘game’ to teach children (4 years onwards) spelling using a poka-yoke technique. The Spellmaster, from J W Spear & Sons – the example here is from 1980 (the Enfield factory was closed after a Mattel takeover in 1994) featured eighty plastic letter tiles, Scrabble-like but larger, with raised pegs underneath, a different pattern for each letter.

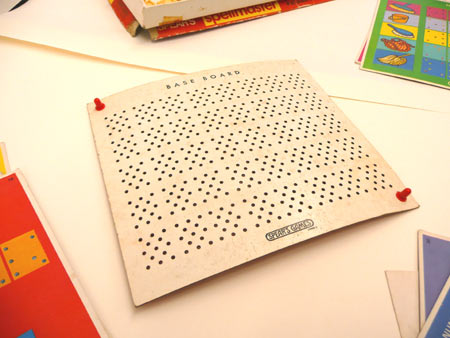

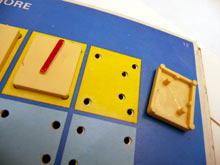

The letter tiles are used to spell the names of objects and concepts (colours, numbers) illustrated on punched cards which fit onto a backing board, the tiles only fitting in their spaces correctly if the pegs pattern aligns perfectly with the punched holes. If the wrong letter is used, the tile doesn’t fit properly and sits at an angle rather than snapping neatly into place. The ‘snap’ of a correctly positioned letter is actually pretty satisfying – surprisingly so, given the combination of plastic (urea formaldehyde, I think) and 30-year old cardboard.

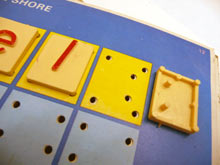

Left: The wrong tile – the pegs do not align with the punched holes. Right: The correct tile – everything lines up. Below: The wrong tile here – note the extra peg on the left-hand edge of the tile, which doesn’t match up with the punched hole, and leads to the tile not sitting down properly.

Letters which could work either way up, such as ‘o’ and ‘s’ have – as would be hoped – symmetrical peg patterns. It’s a simple system, but it’s clever and while not offering any ‘remedial’ function to the child, I would think it’s not too likely that many children would try all 25 other letters assuming the first one didn’t fit. Hence, there is some bias against pure trial-and-error. It’s interesting to think how immediately we might consider a computer-based solution to this kind of design brief today, where a purely physical one would work very well and give a different kind of tactile satisfaction.

Pingback: Code as control | Architectures | Dan Lockton