As mentioned a while back, I’ve been trying to find a way to classify the numerous ‘Design with Intent’ and architectures of control examples that have been examined on this site, and suggested by readers. Since that post, my approach has shifted slightly to look at what the intent is behind each example, and hence develop a kind of ‘method’ for suggesting ‘solutions’ to ‘problems’, based on analysing hundreds of examples. I’d hesitate to call it a suggestion algorithm quite yet, but it does, in a very very rudimentary way, borrow certain ideas from TRIZ*. Below is a tentative, v.0.1 example of the kind of thought process that a ‘designer’ might be led through by using the DwI Method. I’ve deliberately chosen an common example where the usual architectures of control-type ‘solutions’ are pretty objectionable. Other examples will follow.

Basics of the DwI Method, v.0.1

1. Assuming you have a ‘problem’ involving the interaction between one of more users, and a product, system or environment (hereafter, the system), the first stage is to express what your intended target behaviour is. What do you actually want to achieve?

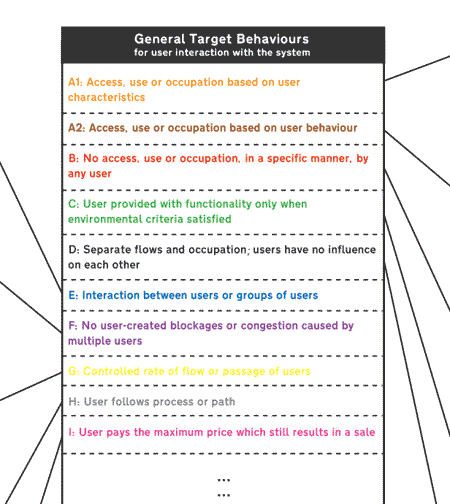

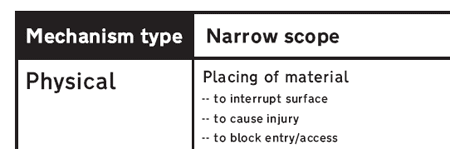

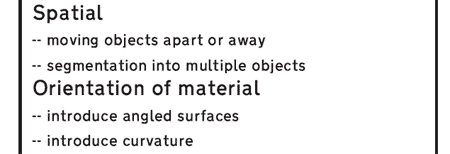

2. Attempt to describe your intended target behaviour in terms of one of the general target behaviours for the interaction, listed in the table below. (This is, of course, very much a rough work in progress at present, and these will undoubtedly change and be added to.) Your intended target behaviour may seem to map to more than one general target behaviour: this may mean that you actually have two ‘problems’ to solve.

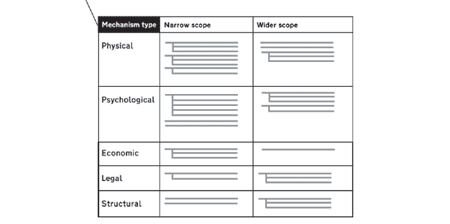

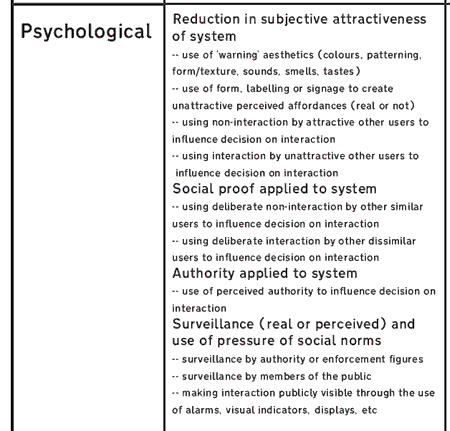

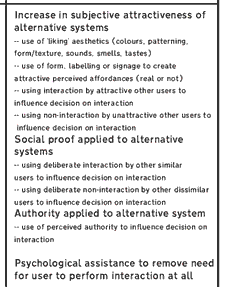

3. You’re presented with a set of mechanisms – loosely categorised as physical, psychological, economic, legal or structural – which, it’s suggested, could be applied to achieve the general target behaviour, and thus your intended target behaviour. Some mechanisms have a narrow focus – dealing specifically with the interaction between the user and the system – and some are much wider in scope – looking outside the immediate interaction. Different mechanisms can be combined, of course: the idea here is to inspire ‘solutions’ to your ‘problem’ rather than actually specify them.

An example

This example is one that I’ve covered extensively on this blog: the most common ‘solutions’ are, generally, very unfriendly, but it’s clear to most of us that the ‘wider scope’ mechanisms are, ultimately, more desirable.

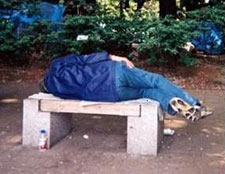

Sleeping on a bench in Hyde Park, London. Photo by David Basanta

Introduction

A number of benches in a city-centre park are occupied overnight or during parts of the day by homeless people. The city council/authorities (‘they’) decide that this is a problem: they don’t want homeless people sleeping on the benches in the park. Expressed differently, their intended target behaviour is no homeless people sleeping on the benches.

So, which of the general target behaviours is closest to this?

Currently the list (disclaimer: v.0.1, will change a lot, letter allocations are not significant) is:

A1: Access, use or occupation based on user characteristics

A2: Access, use or occupation based on user behaviour

B: No access, use or occupation, in a specific manner, by any user

C: User provided with functionality only when environmental criteria satisfied

D: Separate flows and occupation; users have no influence on each other

E: Interaction between users or groups of users

F: No user-created blockages or congestion caused by multiple users

G: Controlled rate of flow or passage of users

H: User follows process or path

I: User pays the maximum price which still results in a sale

While we might think the ‘discriminatory’ implications of A1 and A2 are relevant here given our assumptions about the authorities’ motives, in fact ‘they’ probably don’t want anyone sleeping on the benches, regardless of whether he or she’s actually homeless, just having a lunchtime nap before returning to a corner office at Goldman Sachs, or anywhere in between. They don’t mind someone sitting on the bench (grudgingly, that would seem to be its purpose), as long as it’s not for too long (that’s another ‘problem’, though with very similar ‘solutions’), but they don’t want anyone sleeping on it. It’s not exactly the same problem as preventing anyone lying down (we might imagine a bright light or loudspeaker positioned over the bench, which allows people to lie down but makes it difficult to sleep), but the problems, and most solutions, are very close.

So it turns out that B, ‘No access, use or occupation, in a specific manner, by any user’, best matches the intended target behaviour in this case:

From mechanisms to ‘solutions’

Looking at the diagram (PDF, 25k, or click image below), a number of possible mechanisms are suggested to achieve this target behaviour. (Again, a disclaimer: this is very much work in progress, and many mechanisms are missing at this stage.) There are physical, psychological, economic, legal and structural mechanisms, some with a narrow focus, and some much wider in scope.

I’ll try to pick out and discuss a few mechanisms – physical, psychological and structural (leaving out the legal and economic for the moment) – to demonstrate how they can be applied in the context of the bench example, but first it’s important to note two things:

The most obvious physical mechanism for addressing the issue is the placing of material – to interrupt the surface of the bench, or perhaps even to cause injury (usually not done deliberately with park benches, but surely done, at least in the sense of conditioning the user not to repeat the interactions, with some pigeon spikes, barbed wire, anti-climb and various anti-sit spikes).

Interrupting the surface of the bench is usually done by adding central armrests (which do at least serve another function in addition), as illustrated here:

A new bench with armrests being installed at Richmond Station, just as London Overground takes over from Silverlink; and the Belson Georgetown Bench, “Redesigned to face contemporary urban realities, this bench comes standard with a centre arm to discourage overnight stays in its comfortable embrace.”

Of course, it is possible to sleep on a bench with central armrests, but it’s certainly discouraging, as the Belson quote suggests.

Photo by Rick Abbott

Placing of material could equally be subtractive rather than additive – so interrupting the surface might also suggest removing elements to prevent or discourage sleeping. This could be in the form of removing every (say) third section of a bench, thus making the remaining length too short to lie down on properly (this has been done in some airport lounges), making the benches shorter altogether, or even separating the seats into ‘single-occupancy benches’ – which would seem to be suggested by the spatial mechanism:

“A man tries to sleep on a deliberately shortened bench at the park” – photo from this excellent article by Yumiko Hayakawa discussing anti-homeless measures in Tokyo; ‘Single-occupancy benches’ in Helsinki – photo by Ville Tikkanen

Indeed, simply narrowing the bench (making a kind of perch), and/or removing the backrest from a bench which already has central armrests, so that someone can’t even lean back to doze, would also count in terms of removing material.

Designs suggested by the orientation of material mechanisms are also fairly common – most often, a simply angled seat surface, as used on many bus-stop perches or these benches:

“Can’t Lie Down, Can’t Lean Back – A man has a hard time getting a break on this partitioned, forward-leaning bench at Tokyo’s Ueno Onshi park”. Photo from Yumiko Hayakawa’s article.

The ‘Lean Seat’ by Joscelyn Bingham

Curved surfaces, both convex and concave, can also be employed:

Convex surface tubular bench in Tokyo – photo from Yumiko Hayakawa’s article; Concave surface bus shelter perch in Shanghai – photo by Albert Sun

Convex surface tubular bench in Tokyo – photo from Yumiko Hayakawa’s article; Concave surface bus shelter perch in Shanghai – photo by Albert Sun

And curvature can be combined with the use of armrests (and height – which suggests that spatial might also be expanded to include something like “dimensional change to alter distance between elements of system”) to create something like the ‘Oxford Cornmarket montrosity’, which might prevent people sleeping on it, but certainly doesn’t stop people occupying it in a way the designers didn’t intend:

The ‘benches’ in Oxford’s Cornmarket Street, discussed here and here. Second photo by Stephanie Jenkins

Looking at some of the other relevant physical mechanisms, it’s worth noting that change of environmental characteristic – ‘local temperature change’ – also finds an expression in the convex Tokyo bench pictured above – as Yumiko Hayakawa notes in the original article:

The hard curved surface of this stainless-steel bench, too hot in summer, too cold in winter, repels all but one visitor to Ikebukuro West Park.

We might also think of positioning a street lamp right above a bench – to make it took bright to sleep there easily at night – as a similar tactic in this vein, ‘local illumination change’.

What about the other relevant physical mechanisms? Change of material characteristic could mean a bench that deforms in some way when someone lies on it, or maybe has an uncomfortable surface texture (nails?). But both of these would probably preclude the bench’s use for sitting, in addition to sleeping. Movement or oscillation could suggest a bench which is balanced somehow so that it requires the user’s feet to be on the ground, in a normal sitting position, to keep it stable, and which would fall over (extra degree of freedom introduced) when someone tried to lie down on it, or maybe a bench which is sited on a turntable continually rotating, or a vibrating base, so that the user’s feet on the ground are again needed for stabilising, and someone lying down would fall off. None of these is an especially realistic ‘solution’, but would all address the ‘problem’ even if simultaneously introducing others.

(At this point, we might consider that if the ‘problem’ mainly occurs at night, we might want a bench that only becomes un-sleepable on – or unusable – at night. This would be best addressed by general target behaviour C, ‘User provided with functionality only when environmental criteria satisfied’ – many of the suggested mechanisms will be similar, but with conditional elements to them – if it is dark, or after a certain time, the bench might automatically retract into the ground, or become uncomfortable, if it weren’t already.)

As noted on the diagram (PDF, 25k), I’ve (so far) had a bit of a mental blind-spot in coming up with wider-scope physical mechanisms to address this general target behaviour. The only sensible ones so far relate to applying the placing of material on the approach to the system, so in this case, it might mean putting the bench on an island surrounded by mud, water or spikes and so on, which doesn’t really seem useful. This wider-scope line-of-thinking needs much further development for some types of mechanisms, although it’s fairly obvious where it relates to making an alternative system more attractive.

Narrow-scope psychological mechanisms

Turning to psychological mechanisms, with both narrow and wider scopes, the emphasis pretty much comes down to a ‘stick’ or ‘carrot’ approach: either scare/warn/otherwise put off the user from sleeping on the bench, or make an alternative more attractive/available. It’s about creating unattractive perceived affordances, perhaps, where the physical mechanisms are about removing real affordances.

From the narrow scope point-of-view, some of the applicable psychological ‘solutions’ might include: ‘warning’ potential sleepers off with signage or colour schemes (not that this would do much; it’s more likely to provoke amusement, as in the photo below); making benches which look uncomfortable (whether or not they are); paying(?) scary or unattractive other ‘users’ to hang around the bench to scare people away (which perhaps defeats the object slightly); or, probably most likely, using overt surveillance of the bench, by humans or cameras, which brings in considerations of the legal mechanisms too (and maybe economic, in the form of fines). Another aspect of surveillance is making the (unwanted) interaction visible to other users – using the pressure of social norms to ‘shame’ people into not doing something (positioning the sink outside the bathroom, in a kind of ante-room visible to others, is a good example), but it’s difficult to see how to apply this to the bench example – even if the bench is, say, positioned where lots of people will see the user sleeping on it, the pressure to vacate it is pretty low. This is a kind of ‘public’ feedback; feedback itself is an extremely important psychological mechanism in interaction design, but seems (from my research so far) to be much more applicable to some of the other general target behaviours.

A genuine sign in Orlando, via Boing Boing; and some applicable wider scope psychological mechanisms.

The wider scope psychological mechanisms are much more positive – indeed, more positive than anything else so far in this example. Here, the aim is to make alternative systems – i.e. an alternative to sleeping on the park bench, whatever it might be – more attractive. This is where this sort of thing comes into play:

Sean Godsell’s ‘House in a Park’, a bench that folds out into a rudimentary shelter (above) and (below) Bus Shelter House, which “converts into an emergency overnight accommodation. The bench lifts to reveal a woven steel mattress and the advertising hoarding is modified to act as a dispenser of blankets, food, and water.”

Note that at this level, the alternative systems themselves are attractive (more attractive than sleeping on the park bench) by simply fulfilling users’ needs rather than any psychological ‘tricks’. There is a lesson there.

‘Guerrilla’ responses by users frustrated at heavy-handed anti-user measures don’t directly have a place in the DwI Method, at least as currently constituted, but in this case, for example, providing temporary cardboard seating (/sleeping benches) or even parts that fit over benches with central armrests to permit sleeping once again, as Crosbie Fitch suggests, are worth thinking about:

Perhaps also, for each anti-sit seat design, one could come up with cardboard add-ons that re-enable long-term seating and recumbence. These could be labelled “Temporary Seat Repairs”, “Protective Seat Covers”, “Citizen City Seats”, or something far wittier.

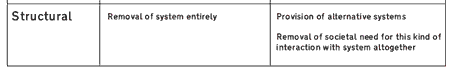

It’s the structural mechanisms which suggest the more large-scale ‘solutions’, from provision of alternative systems (as in the Sean Godsell examples above) to actually removing the need for anyone to sleep rough. Ultimately, of course, that’s a better goal than any of the above – anything discussed in this article – but it’s not really a ‘solution’, rather a desirable aim, or even an intended target behaviour in itself, addressing a social issue rather than a ‘design’ one. Addressing the ‘disease’ rather than merely disguising the symptoms is surely preferable in the long-term.

Alternatively, some cities have simply removed benches altogether where there is a ‘homeless problem…

Benches stripped in Washington DC – “A small homeless population [had grown] there within the past few months”. photo by Fredo Alvarez.

…’removal of system entirely‘ being the structural mechanism there: doing absolutely nothing to help the homeless users, and in the process removing the benches for everyone who uses the park.

Conclusions

The choice of such a negative example for demonstrating this very early version of the Design With Intent Method – where almost all the ‘solutions’ suggested are anti-user and generally unfriendly – reflects, pretty much, where my ‘architectures of control’ research came from in the first place. Most of the examples posted on the site over the past couple of years have generally been about stopping users doing something, forcing them to do something they don’t want to do, or tricking them into doing something against their own best interests – certainly more than have been about more positive efforts to help and guide users.

I thought that using the DwI Method initially to see if I could ‘get inside the head’ (possibly) of the ‘they’ who implement this kind of disciplinary architecture would be a useful insight, before applying the method to something more user-friendly and worthwhile – which willl be the next task.

*As ‘Silverman’ cautioned before, the aim must not be to remove the use of engineering/design intuition – most creative people would not respond well to that anyway – but primarily to inspire possible solutions.

Pingback: Diseño discriminatorio | BLOJER

Pingback: Architecture, urbanism, design and behaviour: a brief review | Design with Intent

Pingback: Europe’s Mean Streets - Intercultural Urbanism